Introduction:

For a long time, whether in injection molding or 3D printing, the crystallinity within parts has typically been consistent throughout. To achieve multiple properties in a single component, it has usually been necessary to rely on multi-material assembly or complex structural designs—approaches that are not only costly but also prone to defects at material interfaces.

Recently, a research team composed of Sandia National Laboratories, the University of Texas at Austin, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) proposed a novel 3D printing method called CRAFT. The related findings were published in the journal Science under the title “Lithographic Crystallinity Regulation in Additive Fabrication of Thermoplastics (CRAFT).”

Research indicates that this technology can spatially regulate crystallinity within a single thermoplastic part simply by adjusting the light intensity during the 3D printing process. This allows the material properties to transition continuously from rigidity to flexibility within a three-dimensional structure, offering a novel manufacturing pathway for applications in soft robotics, energy damping, bioinspired structures, and other related fields.

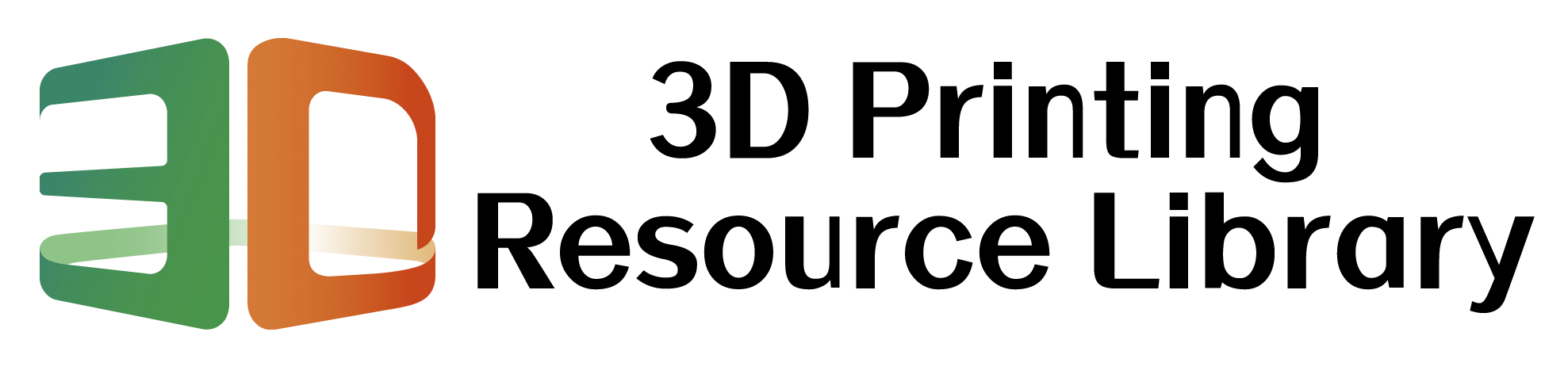

Figure 1: Polymer Chemistry and Crystallinity Regulation via Radiation Intensity

The core idea of CRAFT is not to invent a new type of plastic, but rather to adopt a different approach to “using plastics.” The research team discovered that during the photoinitiated polymerization process, the intensity of light itself can profoundly influence the arrangement of molecular chains, thereby determining whether the material ultimately tends to crystallize more easily or remains more amorphous.

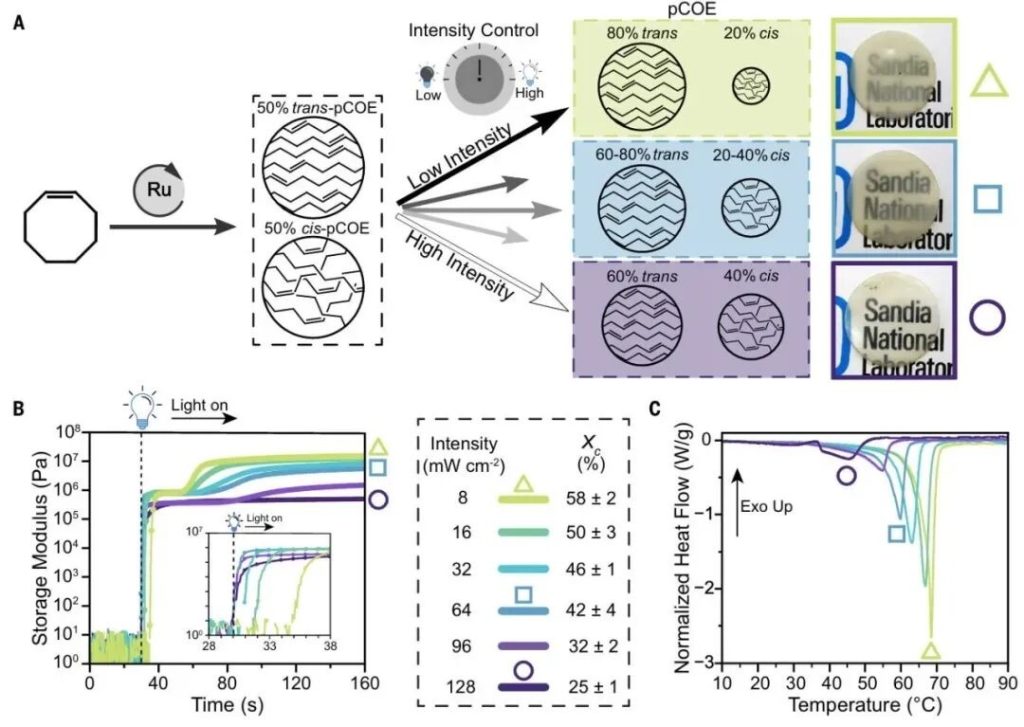

Figure 2: Mechanism of Stereoscopic Control Through Light Encoding

In simple terms, under lower light intensity, molecular chains have more time to rearrange, making it easier to form regular structures. This results in higher crystallinity, causing the material to become stiffer and more opaque, with properties similar to high-density polyethylene. Conversely, under higher light intensity, the crystallization process is suppressed, leading to a softer, more transparent material that behaves more like low-density polyethylene.

Experiments demonstrate that by adjusting light intensity, researchers can achieve a wide range of continuous variations in crystallinity within the same material.

Light is not merely solidifying; it is actively “writing properties.”

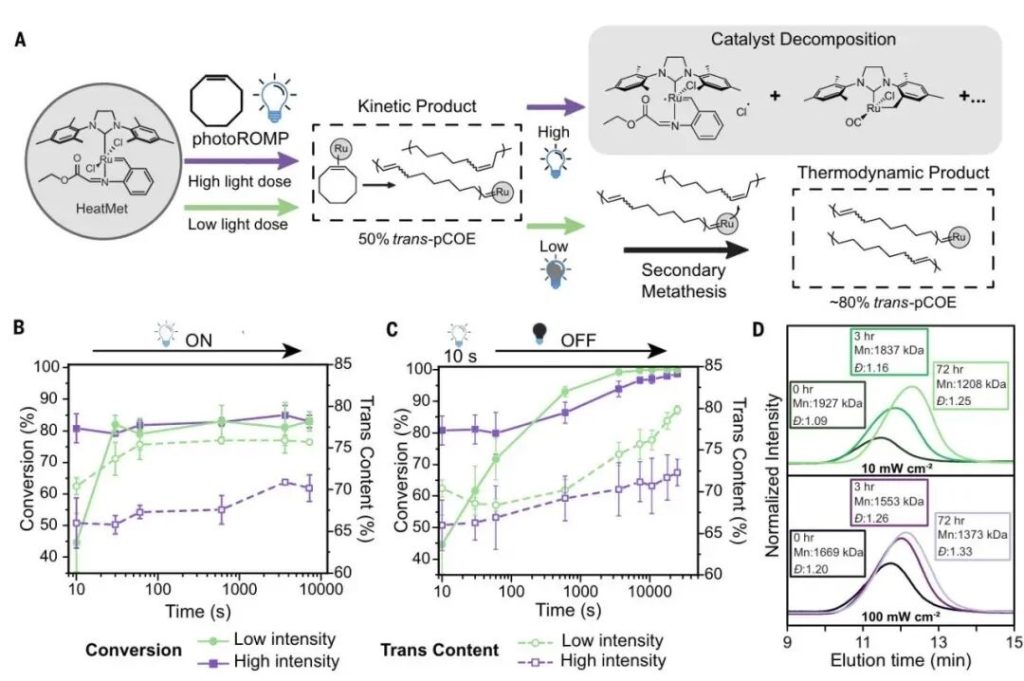

What truly stands out in this work is its integration with commercial DLP or LCD projection-based 3D printing processes. By mapping different light intensities into grayscale patterns, the researchers project these patterns layer by layer during printing, allowing each “voxel” to receive varying doses of light as it solidifies.

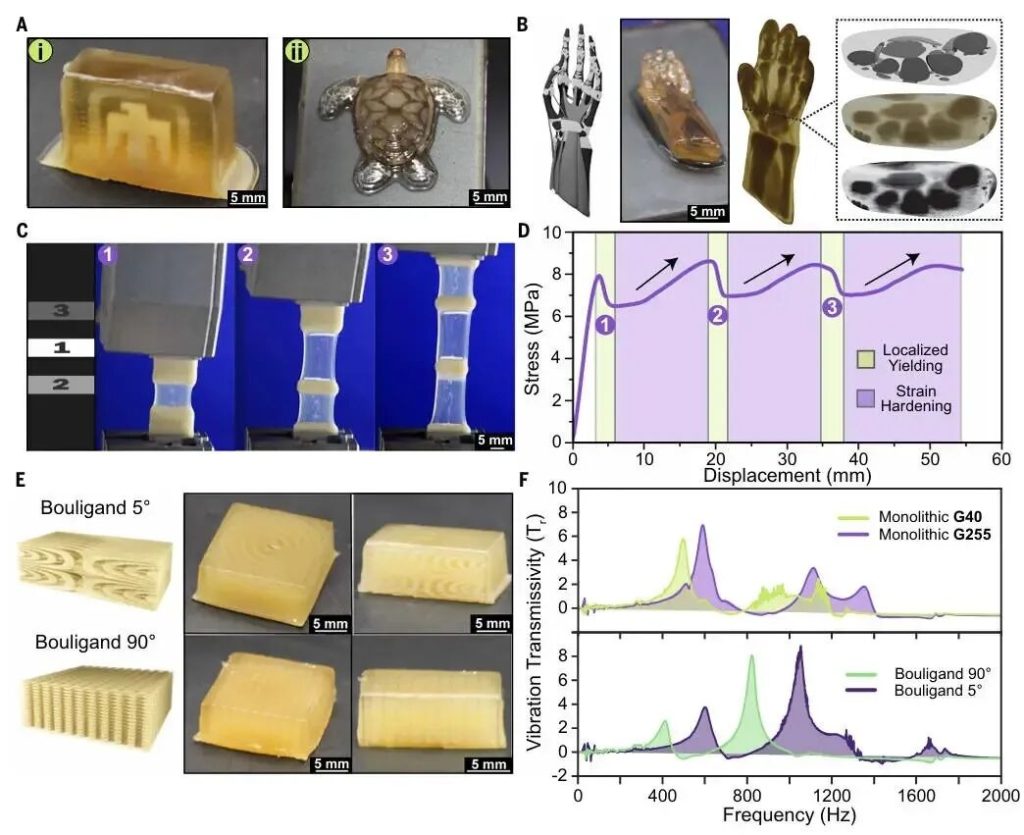

Figure 3: Grayscale Patterning of Crystallinity

In this way, while maintaining the overall shape of the printed object, properties such as crystallinity, stiffness, ductility, and even transparency can be directly encoded into different internal regions. Moreover, these variations are continuous and no longer rely on material splicing. Experimental results show that the spatial resolution of this property modulation can reach the scale of hundreds of micrometers, which is sufficient to support the requirements of most functional structures and bio-inspired designs.

It’s not just a material showcase—it’s truly capable of “getting things done.”

To demonstrate that this method is not merely a laboratory material showcase, the research team further presented multiple engineering application examples.

Figure 4: Multi-material 3D Printing Applications of CRAFT

In a single component, by configuring areas with different light intensities, the printed part yields in a predetermined sequence during stretching, exhibiting segmented mechanical responses. In terms of energy management, drawing inspiration from layered helical structures found in nature, they achieved control over vibration transmission and energy dissipation solely through the design of crystallinity distribution—without altering the shape or adding weight.

In the fields of medicine and biomimetic modeling, this method also enables the simulation of continuous transitions from hard to soft tissues in a single printing process, offering a new manufacturing pathway for creating models that more closely resemble real human anatomical structures.

This Is A Practical Application

Beyond the materials and processes themselves, the research team also focused on the critical challenges of engineering implementation. Researchers from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory pointed out that the difficulty of CRAFT lies not in “whether it can print” but in “whether it can work effectively.”

To address this, they shifted the focus of the computational workflow from “material layout” to “light intensity distribution,” establishing a pipeline that can rapidly convert any CAD geometry into layer-by-layer grayscale exposure instructions. By leveraging parallel computing, they significantly reduced the time required for instruction generation, making rapid design iteration feasible.

LOOKING FORWARD..

From a long-term perspective, the value of CRAFT lies in advancing additive manufacturing from a focus on shape formation to one centered on material property regulation. This technology enables spatially controlled modulation of crystallinity in semi-crystalline thermoplastic materials during the printing process, breaking the limitations of traditional methods where material properties were inherently uniform. By introducing light intensity as a key manufacturing parameter, it achieves synchronous control over material microstructure and three-dimensional forming.

Editor: LI Chen

E: lichen@3dzyk.com